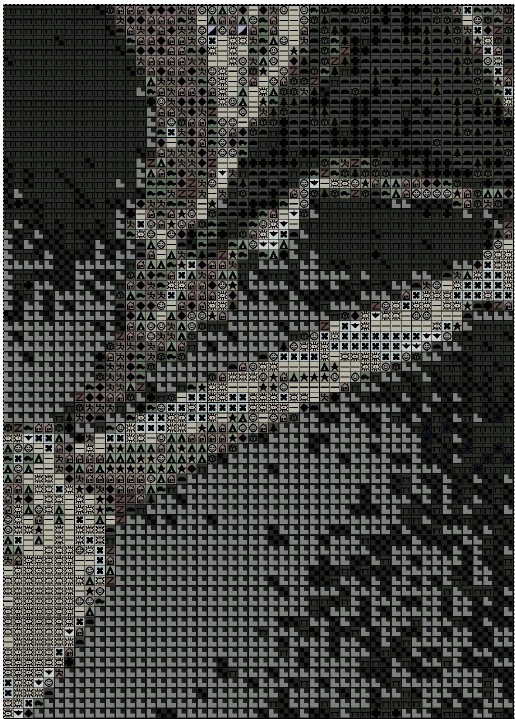

There are two silhouettes of Elizabeth Heyrick. One held by the Society of Friends (Quakers), and a second found in family papers held by Thomas Worthington Clarke, Elizabeth Heyrick’s great nephew who passed away in 1901.1 Unfortunately, these are the only surviving images of Elizabeth Heyrick.

There was a school of thought that portraits were a mark of vanity and, along with the Quaker belief in people’s actions and deeds rather than individuals, Elizabeth Heyrick would not have commissioned a portrait. This means we have little to go on when it comes to knowing what she actually looked like. If you put her name into a search engine, an image of Amelia Opie is often returned. There are other similarities: Amelia Opie became a Quaker and was born in the same year as Elizabeth Heyrick, but there’s no evidence the two women met.

Elizabeth Heyrick’s silhouette shows her hair pulled back into an Apollo knot, a fashion during the 1820s. The hair was then covered by a delicate cap of plain lace and tied under the chin to form a frame of ruffles around the face. This suggests the silhouette was made during the later part of her life.

I’m useless at drawing. The first task was, with much trial and error, to recreate the silhouette, the only surviving image of Elizabeth Heyrick. Software is available to convert an image or photo into a cross-stitch chart. Simply making the base of her silhouette black, with grey for the cap and an off-white background isn’t sufficient. The ‘black’ areas are actually a mix of black, navy, dark brown and dark greens. The colours add an illusion of depth and allow the suggestion the subject was three dimensional rather than flat. The cap is a mix of cream, green-greys and pale grey. Again, the aim is to create the illusion of dimension as well as capture the natural creases and light and shade in the cap. The background is a mix of very pale blue and cream to differentiate it from the cap.

The chart is the image on squared paper with symbols indicating the colour of thread. Cross-stitch is theoretically very simple: each square represents one stitch, all stitches are the same and the cotton material, aida, is pre-punched with holes at the corner of each square where the stitch would go. Conventionally two threads are used to create the stitches on aida of this size. A single thread would reveal the fabric underneath the stitching. Three threads would be too thick. The skill lies in ensuring the top diagonal goes in the same direction on every stitch so that the finish is smooth, in railroading stitches (using a tool such as a needle or specialist tool to separate the threads as the stitch is made) or untwisting the thread, so the stitches lie flat, and keeping count.

Progress is not quick. The first 100 stitches look good because the comparison is with an empty piece of material. The second 200 stitches double the previous stitched area. However, after 1000 stitches, 100 new stitches look a little lost and there’s a point, usually around two-thirds of the way into a project where motivation sags. I stitch in spare time in between a job and other commitments, which slows progress even more.

The finished stitching is handwashed, pressed and ready for framing. I measure the finished stitched area, leave a small gap and order the mounts and frame online. For the colour of the inner mount, I chose a sage green as, after black, green is the most frequently occurring colour. Black has associations with mourning. Green is a more positive colour, and sage is associated with wisdom, balance, emotional strength, which seems highly appropriate for Elizabeth Heyrick. The walnut frame colour seemed the best complement.

1 “Elizabeth Heyrick: the Making of an Anti-Slavery Campaigner”, Jocelyn Robson (Pen & Sword Books, 2024), pp.xx-xxi