Who do you picture when you hear the words ‘slave trader’? A ruthless captain on the deck of a ship? A callous merchant in a coastal fort? These images, while true, are only a fraction of the story. To truly understand the history of the slave trade, we must realise that its evil was a systemic web of complicity, stretching from the palaces of London to the parlours of ordinary British families.

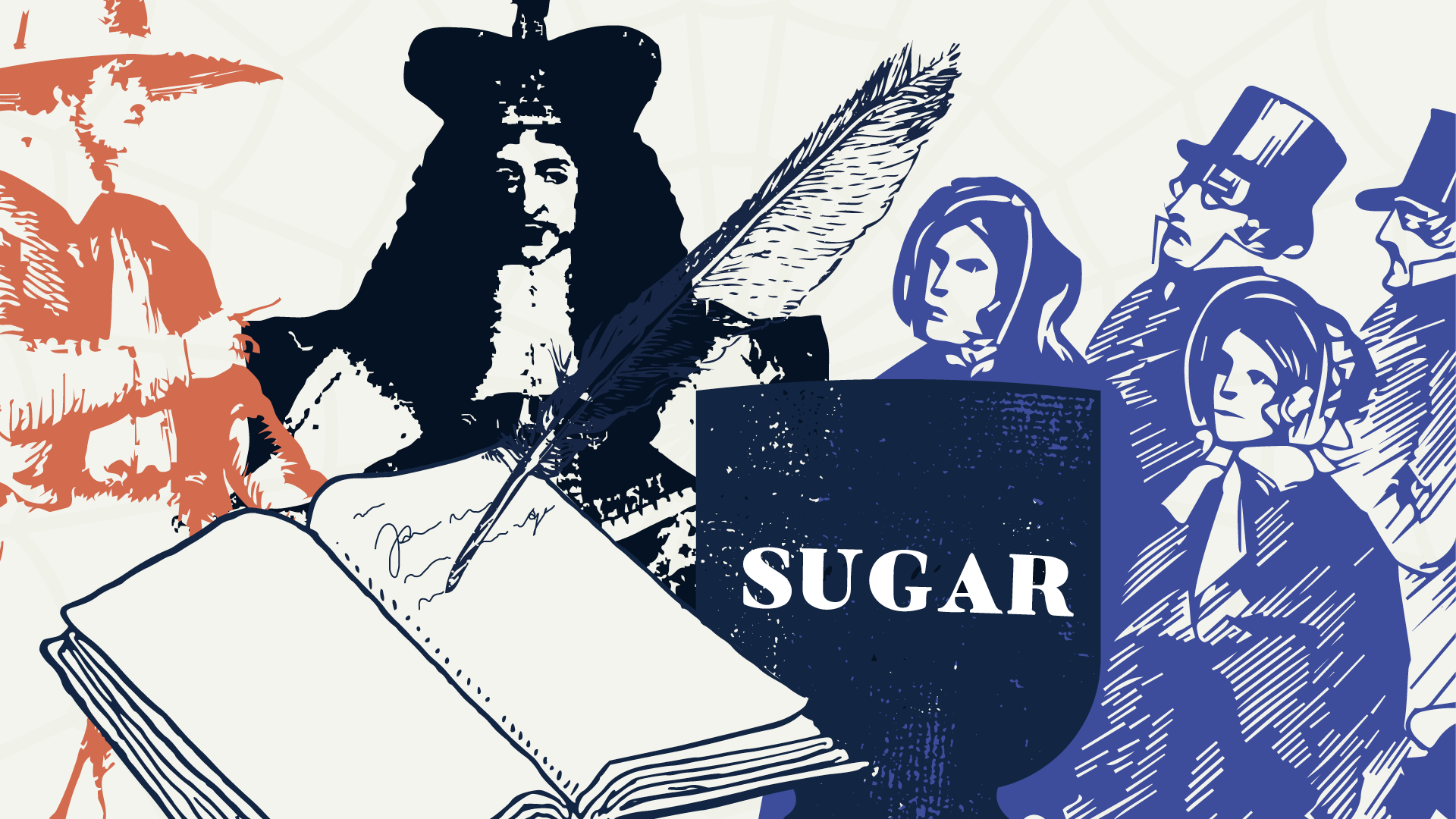

The villainy wasn't just in the act of chaining a person, but in the signing of a ledger, the passing of a law, and even the stirring of sugar into a cup of tea.

The "Respectable" Profiteers: Financing the Slave Trade

Imagine walking through the bustling financial centres of 18th-century Liverpool or Bristol. The men you see in fine coats, striking deals and signing papers, were the engine of the British slave trade.

These were the financiers and merchants who saw human trafficking as just another commodity. In Bristol, this included figures like Edward Colston, a high-ranking official in the Royal African Company whose immense profits from the trade were later used to fund schools and charities across the city. He, along with the powerful Society of Merchant Venturers, represents the deep intertwining of Bristol's civic life and the slave economy. Similarly, in Liverpool, the influential Heywood banking family built a financial empire by funding voyages that turned human lives into economic assets.

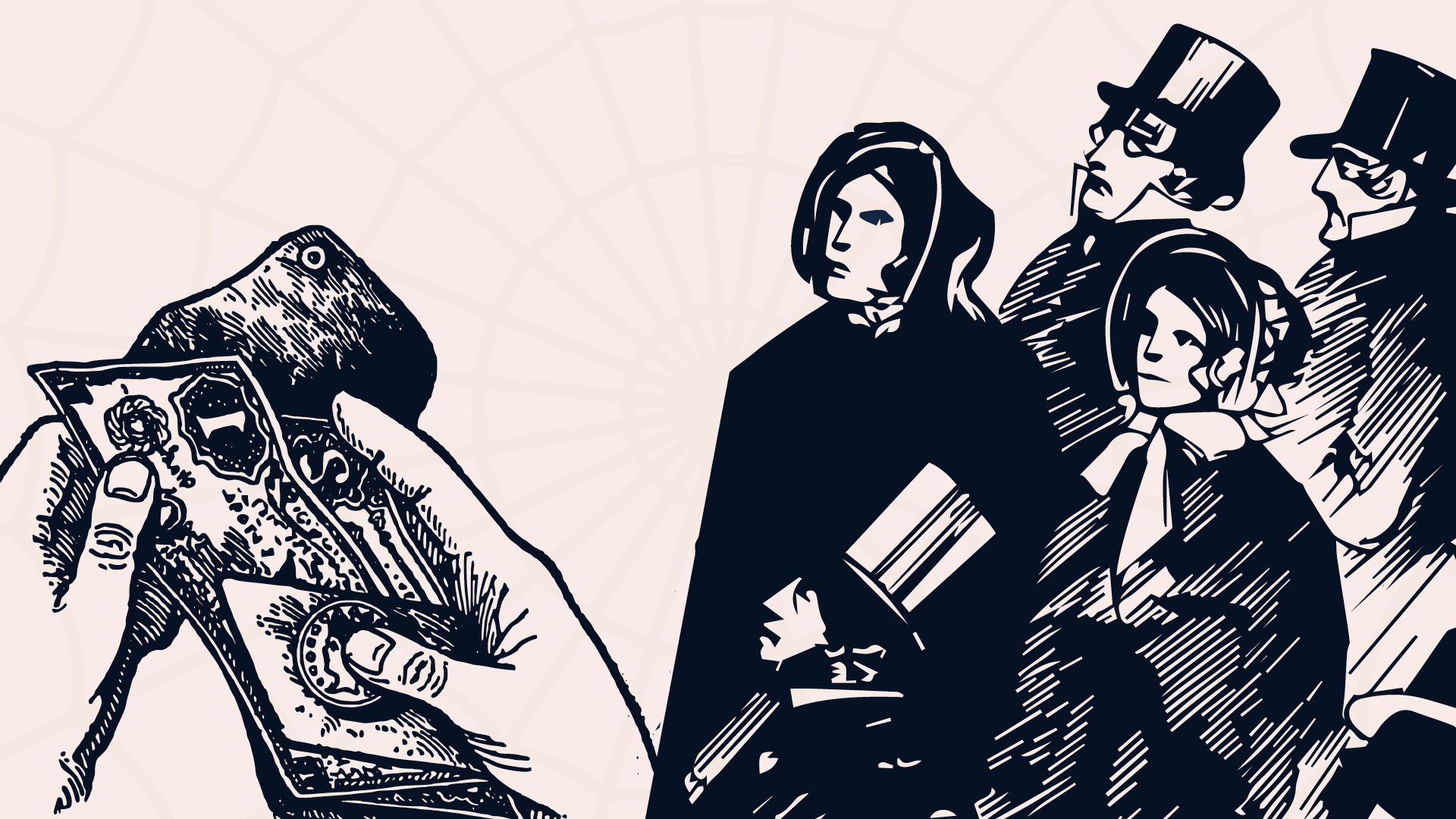

Then there were the insurers. In a quiet room at Lloyd's of London, underwriters would calculate the odds on a slave voyage. They treated people as cargo, a risk to be managed. The infamous case of the slave ship Zong in 1781 lays this bare. The captain ordered 132 enslaved Africans to be thrown overboard, alive, claiming a shortage of drinking water. However, the subsequent court case wasn't about murder; it was an insurance dispute over "lost cargo." This brutal event and its following consequences represent the ultimate dehumanisation, codified in a business contract.

The Pillars of State: Royal and Political Complicity

This entire system of forced labour was propped up by the highest authorities in the land. Kings, queens, and governments were not just passive bystanders; they were active participants. King Charles II granted a Royal Charter to the "Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa", while Parliament passed laws that codified the system, such as the Trade with Africa Act of 1698, which opened up the slave trade to all English merchants and formalised its role in the nation's economy.

When the abolitionist movement gained momentum, who stood in the House of Lords to defend the slave trade? The Duke of Clarence (the future King William IV), who used his royal position to argue for the continuation of a trade that made so many of his peers rich. Parliament passed laws that protected the institution of slavery, using the full weight of the British state to legitimise and defend a system of torture.

The Villain in the Mirror? Everyday Complicity

This may be the most uncomfortable truth of all. The web of villainy reached directly into the homes of ordinary people across Britain.

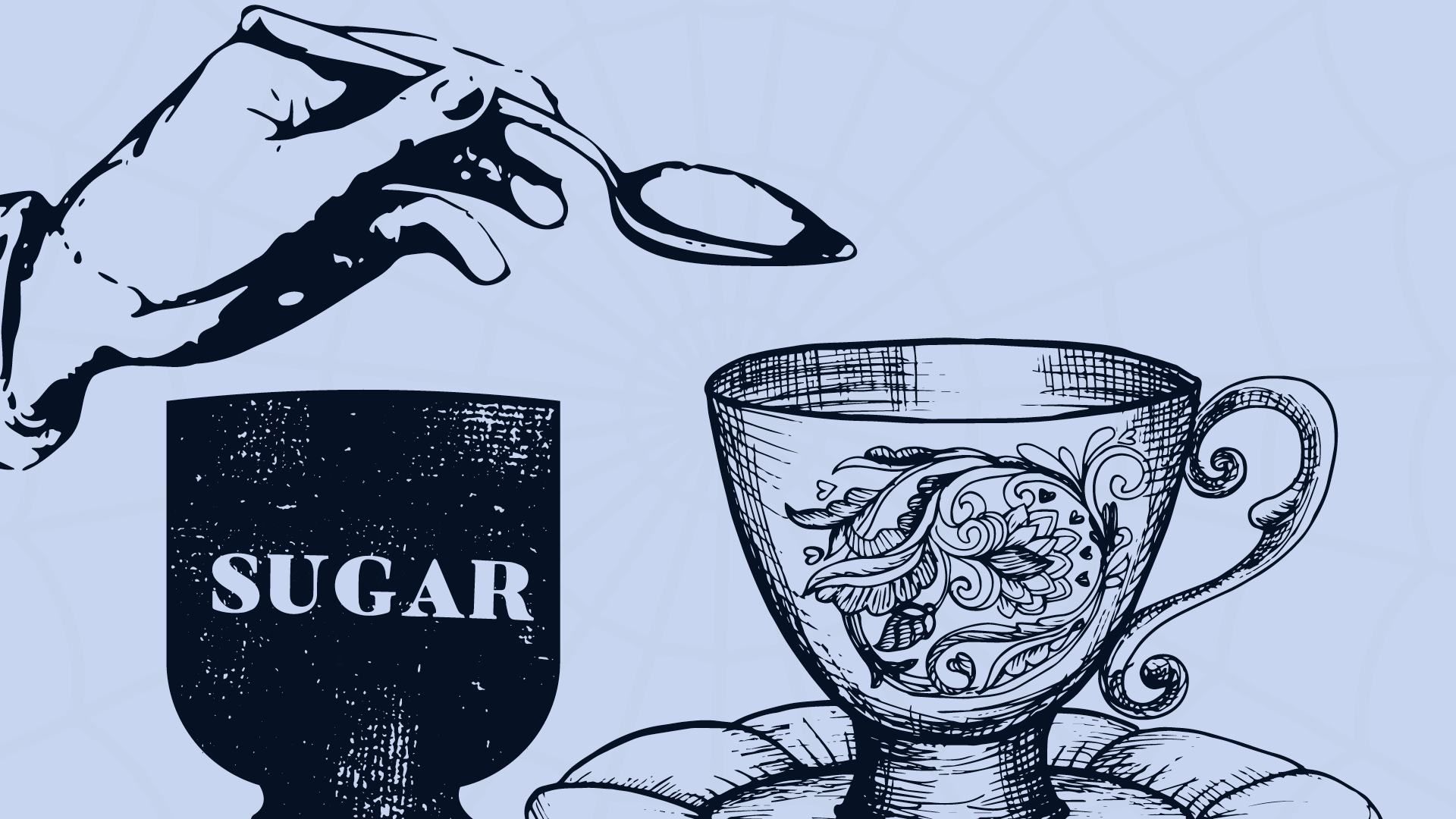

Take a moment and picture a typical Georgian tea table. The tea, the coffee, the fine clothes, and most importantly, the sugar, were all products of enslaved labour. The sweet tooth of a nation created a ravenous demand that was satisfied by the brutal plantation system.

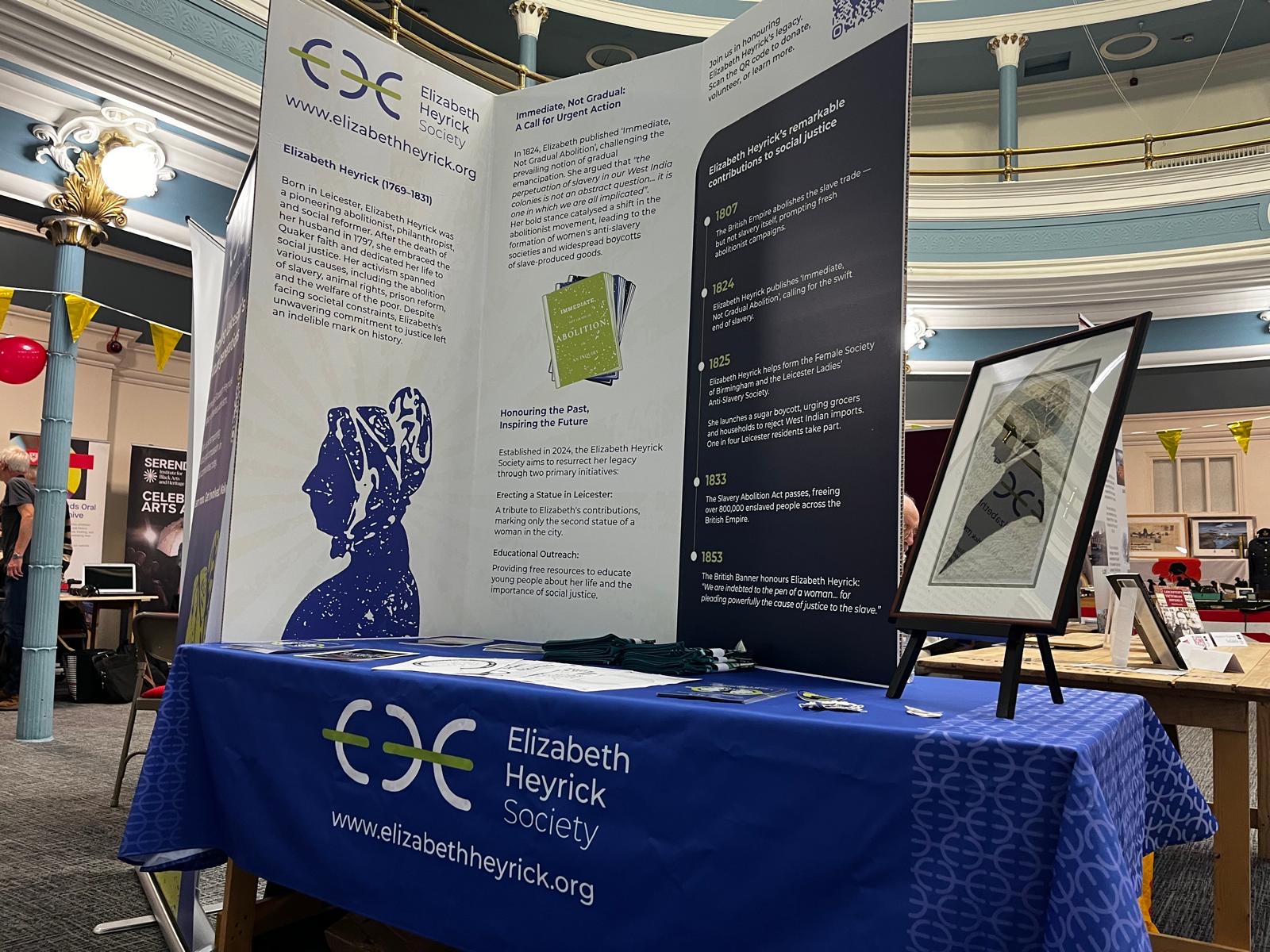

This is why the work of abolitionists like our own Elizabeth Heyrick was so radical. Her 1824 pamphlet, Immediate, not Gradual Abolition, called for an end to compromising with slave owners and helped energise a massive boycott of West Indian slave-grown sugar around 1825. The campaign was not just about refusal; it was about providing a moral choice. Abolitionists urged people to switch to sugar imported from the East Indies, where it was produced by free labour.

Hundreds of thousands of people, especially women, made that choice, directly hitting the profiteers in their pockets. They understood that to consume the product was to be complicit in the crime. Those who heard the abolitionists' pleas but continued to sweeten their tea with slave-grown sugar were choosing convenience over conscience.

The silence of millions more, the apathetic majority who knew of the horrors but did nothing, created the social acceptance that allowed the trade to flourish for centuries. This passive complicity was as vital to the system as any investor's gold.

The Echoes of Complicity Today

It is easy for us to judge the past, to condemn the plantation owner and the silent consumer. But the structure of that complicity has not vanished; it has simply changed its form.

The web of complicity that tied a British housewife's sugar bowl to the suffering on a Caribbean plantation echoes in our modern world. It connects the smartphone in our pocket to child labour in cobalt mines and the cheap t-shirt in our wardrobe to the exploitation of garment workers.

But it goes deeper. That same web entangles us when we buy products from companies operating on illegally occupied land, or when our own banks and pension funds invest in enterprises that enforce systems of segregation and displacement. When we remain silent, our consumption and our investments risk making us passive contributors to a humanitarian catastrophe.

The history of the slave trade is not just a lesson about the past. It is a mirror. Honouring the legacy of radical abolitionists like Elizabeth Heyrick means more than just remembering their fight. It means applying their demand for moral courage to our own lives, questioning what we buy, where our money is invested, and what we demand from our leaders in the face of profound injustice and violations of international law.